Summary

I turned a 2000s arcade-style racing game into a Gym environment by injecting custom hooks via a DLL and sharing pixel buffers with Python using shared memory. Unlike most RL environments, this project is based on a closed-source Windows game from the early-2000s, requiring custom DLL injection, memory sharing, and real-time synchronization.

I then trained reinforcement learning agents from pixels using PPO and other algorithms. This project combined reverse engineering, C++/Python interprocess communication, and deep reinforcement learning.

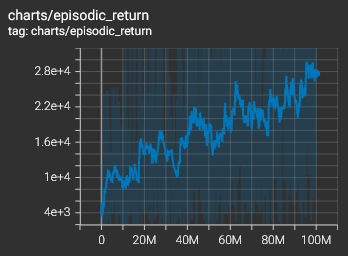

The trained agent stabilizes at an average score of ~20,000 points per episode after 100M steps, with high variability (hundreds to 80,000 points) and convergence to a suboptimal but stable policy. Although mastery of this environment is deceptively complex, the agent learned interpretable behaviors such as avoiding civilians and destroying enemies, but still struggles with rear-end collisions and long-term planning.

Skills involved

- Custom Gym environment creation

- Deep RL training pipeline from raw pixels (Proximal Policy Optimization, Stable Baselines 3)

- Profiling, debugging, and experiment logging

- Windows API and DLL injection (function hooking)

- Shared memory & interprocess synchronization (Python & C++)

- Reverse engineering of legacy game binaries

Introduction

This project showcases how I built a reinforcement learning (RL) agent to play a 2000s game. The goal is to demonstrate practical understanding of RL algorithms, environment design, and training evaluation. Although not intended as research, the work highlights key aspects of building and refining an RL system in a complex setting.

Note: This post covers the choices, design, and technical challenges behind the project. Some familiarity with reinforcement learning and Windows’ low-level mechanisms will help, but you can skip straight to the results if you prefer.

What is Highway Pursuit?

Highway pursuit by Adam Dawes is an arcade-like game from the early-2000s where the player drives a car along a highway from a top-down perspective and gains score as the traveled distance increases. The road is filled with civilian and enemy vehicles, both of which may collide and damage the player. Destroying civilian vehicles temporarily prevents score gains, while destroying enemies rewards the player with a flat score increase.

Motivations

My main motivation for this project was to gain hands-on experience with the reinforcement learning workflow and to explore behaviors learned through this method on an existing, human-playable problem. I was also technically interested in adapting an existing, non-RL-compliant application into a real-time Gym-compatible environment.

Games offer ideal settings for this experimentation: they’re fun, challenging, and provide intuitive ways to interpret and evaluate what an agent has learned. In particular, Highway Pursuit has several properties that make it well-suited for RL:

- The player’s score provides a dense and straightforward reward signal

- The game’s dynamics are relatively simple, making basic behaviors easy to learn

- It is computationally lightweight and can be significantly accelerated on modern machines.

Adapting the Game to Reinforcement Learning

In this first section, I outline the technical challenges and choices involved in turning the Highway Pursuit into a Gym-compatible environment.

Observations, actions and rewards

Creating a custom Gym environment requires defining the observation space, action space, and reward function.

- For technical simplicity, raw pixels are used as observations. While this simplifies the implementation, it also introduces challenges: meaningful features are harder to learn, and the environment becomes partially-observable as not everything happening in the game is visible on screen.

- Actions are binary vectors corresponding to keyboard keys (accelerate, left, right, brake, shoot).

- The in-game score serves as the reward function. It doesn’t require shaping, since it’s already dense: the score increases as the player drives forward or destroys enemies, both of which are fairly common occurrences (even with a random policy).

Architecture

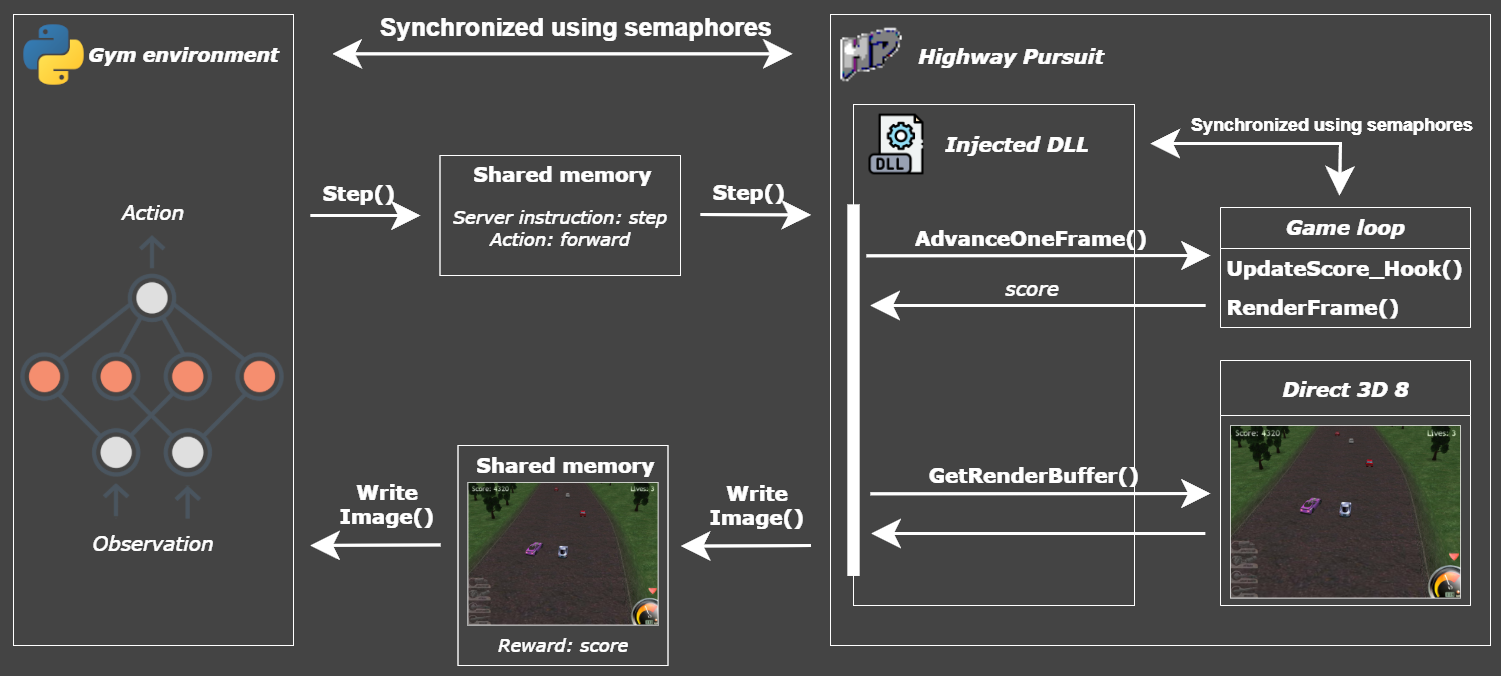

The project consists of two main components:

- A Python package that provides a Gym-compliant environment and forwards instructions such as

resetorstepto the game - A game-side server, injected into the game process, which synchronizes the game and executes the received instructions

The top priority guiding technical decisions is data collection speed, i.e., making the environment as efficient as possible. To achieve this, the server is injected into the game process using a DLL and controls the game via function hooks.

Communication between the Python package and the server also needs to support high data throughput (particularly for transmitting raw pixels) so shared memory is used for interprocess communication, enabling fast and efficient data transfer.

Technical Details

This section provides an in-depth look at the modifications made to the game and the technical implementation of the environment, using the Windows API and its older 3D engine, Direct3D 8. Knowledge of these tools will help, feel free to skip ahead if you prefer.

One of the most important modifications made to the game is enabling accelerated gameplay. The simplest and most effective solution is to hook time-providing functions and replace their return values with fully controlled custom variables. The game uses the Windows’ Performance Counter to track elapsed time, which means that hooking

QueryPerformanceFrequencyandQueryPerformanceCounteris sufficient to implement custom time control.

Each environment step corresponds to one elapsed frame, advancing the performance counter by 1/60th of a second. This keeps the simulation at a constant 60 FPS while allowing unlimitedstepcalls per real second.Another core modification involves synchronizing the game’s main loop with the server. This is achieved using a pair of semaphores, which ensures that the main loop is executed exactly once per instruction sent to the server.

Efficiently accessing raw pixel data is also critical. The game runs on Direct3D 8 (D3D8), and the most efficient method to retrieve the rendering buffer is to call D3D8 functions and copy the buffer into shared memory. This was challenging because it requires both properly understanding D3D8’s API and figuring out the specific rendering settings used by the game.

Accessing D3D8 functions, in particular, enables lowering the rendering resolution. This both improves the game performance and speeds up data transmission. It also enables the use of windowed mode, which is key to running several environments in parallel on a single machine.

Finally, one last key modification is to hook several internal game functions to support both data collection (e.g., retrieving the score) and full control over episodes (e.g., starting a new game or respawning the player when

resetis called).

Main challenges

Turning the game into a reliable RL environment involved overcoming several challenges:

- Locating and reverse-engineering internal game functions and variables, which required understanding assembly-level logic such as calling conventions.

- Interfacing with Direct3D 8, which is an outdated framework that only runs on Windows 10 and 11 via compatibility wrappers:

- This makes D3D8 functions non-static, requiring dynamic resolution of the vtables to locate function pointers without depending on a specific wrapper implementation.

- It can also introduces instability when using system-level hooks like

QueryPerformanceCounter, as some wrapper versions use the Performance Counter internally during initialization. This is adressed by enabling system-level hooks post-initialization.

- Debugging very low-level code like game function hooks is non-trivial. It requires a clear understanding of existing assembly code, how custom code is injected, and what might cause crashes (which often occur without any indication of what went wrong).

Takeaways

Beyond the technical implementation, this project was a great opportunity to gain hands-on experience in multiple low-level systems areas.

- Gained hands-on experience with reverse engineering, inter-process communication, and synchronization mechanisms.

- Despite its age, working with D3D8 offered valuable insight into the inner workings of rendering engines.

- Gained practical experience in building a custom Gym environment from scratch, including observation, action, and reward design, as well as performance optimization.

Training an Agent

In this section, I outline how I trained an agent to play Highway Pursuit using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), along with the preprocessing steps and results.

Preprocessing

This environment uses raw pixel data as observations, with a minimal supported resolution of 320×240, which is quite large for efficient pixel-based training. Several preprocessing steps were applied to improve training performance:

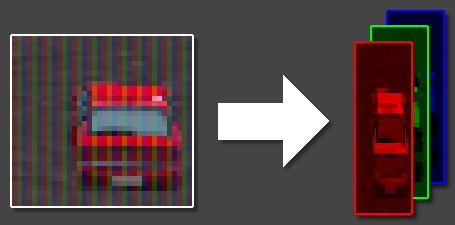

- Resolution reduction: To speed up training, it is beneficial to reduce the number of pixels. A straightforward option would be to convert the image to grayscale. However, color carries critical information in this game, especially for distinguishing entities (e.g., civilian vehicles from enemies).

I therefore chose to instead downsample the image along the x-axis, retaining color information. The rationale is that the game’s dynamics are primarily vertical: entities flow from the top to the bottom of the screen as the player drives forward. Because most meaningful objects are wide enough, horizontal downsampling does not destroy critical information. To keep color cues, I implemented a simple scheme where each column in the downsampled image keeps only one color channel (red, green, or blue), in a rotating pattern. This results in a compressed image with fewer pixels while retaining a sense of color.

- Standard preprocessing techniques (adapted from the Atari RL preprocessing pipeline):

- Observation normalization: scaling pixel values to [0, 1].

- Frame stacking: 4 consecutive frames are stacked to capture motion and temporal dependencies. To reduce redundancy, frames are sampled every 3 steps (frame skip = 3).

- Reward normalization: stabilizes PPO updates and improves learning speed.

Algorithms

The primary algorithm I focused on is Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), which offers a solid baseline for reinforcement learning from high-dimensional inputs. PPO is widely used due to its stability, sample efficiency, and relatively low sensitivity to hyperparameters compared to algorithms like vanilla policy gradients or DDPG.

I used the PPO implementation from a tutorial by Weights & Biases (GitHub), slightly modified to ensure compatibility with my custom environment and to include performance profiling metrics.

Training used multiple parallel environment instances on one machine to speed up rollout generation.

Network architecture

PPO is an actor-critic method, which means it learns both a policy and a value function. With high-dimensional raw pixel inputs, it is beneficial and common practice to use an architecture where the convolutional layers are shared between the actor and the critic for better sample efficiency.

The architecture I used consists of:

- Shared convolutional base with 3 convolutional layers and 1 hidden MLP layer

- Two MLP heads, one for the actor (policy output) and one for the critic (value function prediction)

This setup closely follows architectures used for Atari-like environments, where inputs are raw pixel frames and efficient shared representations are crucial.

Results & Learned Behaviors

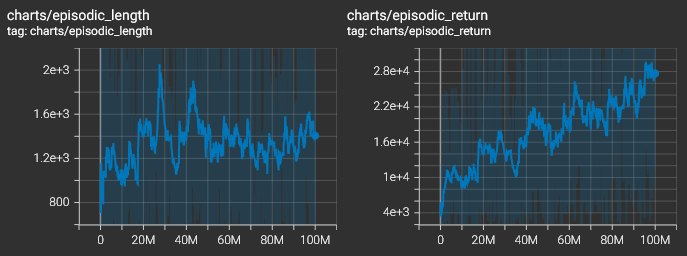

After 100M training steps, the agent achieves an average score of approximately 20,000 points per episode.

Performance remains unstable: while some episodes reach up to 80,000 points, others drop to only a few hundred due to random high-difficulty situations (e.g., dense traffic, enemies approaching from behind). The average score steadily increases during training, albeit slowly, while the average episodic length plateaus after a few million steps.

This suggests that the agent quickly reaches a locally optimal policy, which continues to improve during training but does not explore strategies focused primarily on survival or progressing further into the game (where new events are unlocked once a certain distance has been driven).

The agent was able to learn several interesting behaviors from training runs using 30M to 100M environment steps:

- The agent learns to move forward and stay on the road.

- It learns to consistently target enemies while rarely destroying civilian vehicles.

- It discovers that destroying enemies in quick succession yields higher rewards (due to score multipliers).

- In longer training runs, the agent learns to regain health by driving slowly on the side of the road, where it avoids most collisions.

However, the learned policies also exhibit clear limitations:

- The agent never attempts to drive at high speeds, unlike human players who favor steep acceleration. This can be explained by higher speeds not being well represented during early training when policies are close to random, or the risk being too difficult to manage. Driving at slow-speed also helps enemies approach the player, which increases short-term score gains.

- The agent instantly forgets enemies as soon as they leave the visible screen area. This suggests it lacks memory and cannot track entities over time, a direct consequence of the environment being partially observable and the current network architecture lacking recurrent memory.

- It struggles with rear-end collisions, where another entity enters the screen from below and crashes into the player. Human players rarely experience this, as faster driving speeds naturally avoid these types of collisions.

These results highlight how RL agents trained from pixels can discover semantically meaningful strategies, but also exposes how architectural choices (e.g., memory) and how the distribution of training samples significantly impact what they learn.

One of the limitations of this environment is that, while optimized, it still runs too slowly for large-scale hyperparameter experimentation and tuning (on my current available hardware). Learning significant behaviors involved training the agent for at the very least 10 hours, making comparison of different configurations difficult.

Performance & Profiling

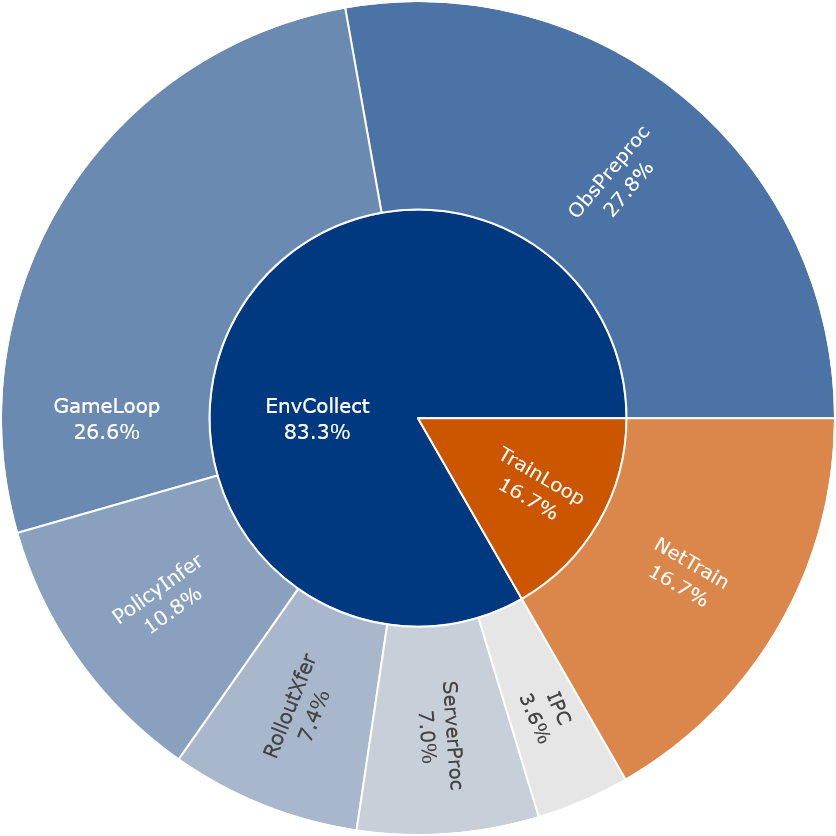

Profiling shows that the majority of computation time is spent on environment rollouts, including simulation, rendering, and observation preprocessing.

- EnvCollect - Time spent generating rollouts by interacting with the environment.

- ObsPreproc - Observation preprocessing (e.g., resizing, normalization, frame stacking).

- GameLoop - Game loop, including physics simulation and rendering.

- PolicyInfer - Policy network forward pass during action selection in rollouts.

- RolloutXfer - Transfer of rollout observations from CPU to GPU for inference.

- ServerProc - Computation performed on the environment’s server-side logic (injected DLL main thread).

- IPC - Interprocess communication overhead between server and RL process.

- TrainLoop - Time spent in the training phase of the RL algorithm (excluding environment interaction).

- NetTrain - Policy and value network loss computation and parameter updates.

This profiling was done while running multiple parallel instances of the environment to maximize data collection throughput. Even with parallelism, interacting with the environment dominates runtime. This suggests that distributing rollouts across more machines or decoupling data collection from weight updates (e.g., with asynchronous or offline RL approaches) could significantly reduce training time.

Alternative Algorithms

While PPO was the main focus, I also experimented with other algorithms using Stable-Baselines3, while keeping the same preprocessing and similar architecture:

- DQN

- A2C

- Recurrent PPO (PPO + RNN)

However, the differences in learned behavior and overall performance were minimal. This was likely due to:

- Limited training durations (typically 10M steps)

- Potential preprocessing and architecture bottlenecks dominating learning outcomes

- The environment being deceptively difficult to master and explore

- Unoptimized hyperparameters

Note: I plan to include the tensorboard training curves of those algorithms, comparing them using similar hyperparameters.

Takeaways and Future Work

Training an RL agent was a great opportunity to put theoretical concepts into practice:

Learned crucial PPO implementation details.

Gained hands-on experience with the deep RL training workflow: preprocessing, network architecture, hyperparameter tuning, performance monitoring, and model saving.

Learned that preprocessing and overall architectural decisions play a major role, in addition to hyperparameter tuning:

- Normalizing inputs (observations, rewards) is essential for the network to learn efficiently.

- The number of stacked frames and their frequency greatly influence what the agent can or cannot learn. (Wider windows generally led to decisions yielding higher rewards, while higher frequencies resulted in tighter control and increased survivability.)

- Although not fully explored, learning rate annealing and discount factor tuning appeared essential for training efficiency.

Despite achieving a few hundred steps per second, the environment remains slow due to the high-dimensional observation space and the game’s engine not being suited for maximum performance. This unfortunately limited the number of training runs and prevented meaningful comparisons of hyperparameters and architectural decisions. For future learning-oriented RL projects:

- I plan to use smaller-scale, fast and lightweight environments that allow for faster iteration and more thorough comparisons of different configurations.

- I will consider cloud computing solutions for computationally heavier environments.

When learning from scratch, the agent quickly adapts to a strategy that fits the initial sample distribution (slow-driving speeds) and rarely deviates from it. In the future, it would be worth exploring ways to mitigate this, such as:

- Longer training times

- Carefully chosen hyperparameters

- Algorithms that encourage exploration or use curiosity-based reward signals

- Methods like imitation learning or transfer learning

A future improvement is to address the partial observability of the environment using architectures suited for long-term dependencies (e.g., RNNs, LSTMs, GRUs).

Overall, this project deepened my understanding of the practical trade-offs in deep RL. While the environment’s complexity introduced many challenges such as partial-observability, exploration and sample efficiency, I gained key insights as to why they occur and plan to explore them in future projects.